There are the early-bloomers and late-bloomers. Here's the article from Wired. It's interesting reading.

Galenson collected data, ran the numbers, and drew conclusions. He selected 42 contemporary American artists and researched the auction prices for their works. Then, controlling for size, materials, and other variables, he plotted the relationship between each artist’s age and the value of his or her paintings. On the vertical axis, he put the price each painting fetched at auction; on the horizontal axis, he noted the age at which the artist created the work. When he tacked all 42 charts to his office wall, he saw two distinct shapes.

For some artists, the curve hit an early peak followed by a gradual decline. People in this group created their most valuable works in their youth – Andy Warhol at 33, Frank Stella at 24, Jasper Johns at 27. Nothing they made later ever reached those prices. For others, the curve was more of a steady rise with a peak near the end. Artists in this group produced their most valuable pieces later in their careers – Willem de Kooning at 43, Mark Rothko at 54, Robert Motherwell at 72. But their early work wasn’t worth much.

Galenson decided to test the robustness of his conclusions about artists’ life cycles by looking at variables other than price. Art history textbooks presumably reflect the consensus among scholars about which works are important. So he and his research assistants gathered up textbooks and began tabulating the illustrations as a way of inferring importance. (The methodology is analogous to Google’s PageRank system: The more books that “linked” to a particular piece of art, the more important it was assumed to be.)

When Galenson’s team correlated the frequency of an image with the age at which the artist created it, the same two contrasting graphs reappeared. Some artists were represented by dozens of pieces created in their twenties and thirties but relatively few thereafter. For other artists, the reverse was true.

Galenson, a classic library rat, began reading biographies of the artists and accounts by art critics to add some qualitative meat to these quantitative bones. And then the theory came alive. These two patterns represented two types of artists – indeed, two types of humans.

The insight was so powerful that Galenson soon turned his full attention to the subject. He elaborated his theory in 24 additional papers and set down his findings in a pair of books, Painting Outside the Lines: Patterns of Creativity in Modern Art, published in 2001, and Old Masters and Young Geniuses: The Two Life Cycles of Artistic Creativity, published earlier this year.

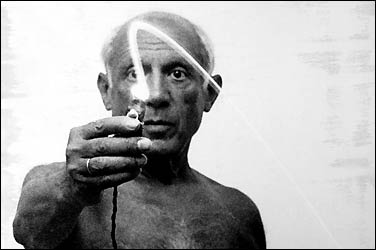

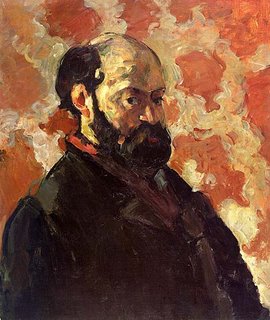

Pablo Picasso and Paul Cézanne are the archetypes of the Galensonian universe. Picasso was a conceptual innovator. He broke with the past to invent a revolutionary style, Cubism, that jolted art in a new direction. His Demoiselles d’Avignon, regarded by critics as the most important painting of the past 100 years, appears in more art history textbooks than any other 20th-century piece. Picasso completed Demoiselles when he was 26. He lived into his nineties and produced many other well-known works, of course, but Galenson’s analysis shows that of all the Picassos that appear in textbooks, nearly 40 percent are those he completed before he turned 30.

Now that it is spelt out, it seems bloody obvious.

Japanese poet Shiki Masaoka carried out a similar assessment of Japanese writers back in the late 19th century and concluded a writer ought to live longer. Those who are long-lived produced the most important body of work, according to Masaoka. Of course he was dead at 35. Yet, he was a conceptualist who radically updated Japanese poetry, and one could say he had done the big thing that radically redefined his field by the time of his earrly death.

I guess, while the claim is intuitively obvious, it needed a rigorous empirical examination.

No comments:

Post a Comment