This is despite the usual current objections.

Here's the article.

NASA Administrator Mike Griffin, overruling objections from the agency's chief engineer and safety office, cleared the shuttle Discovery for launch July 1 on a mission to service and resupply the international space station. The flight also will clear the way for the resumption of station assembly later this fall and deliver a third full-time crew member to the international outpost.Here we go again.

The objections centered on the risk posed by launching Discovery with foam buildups around brackets on the ship's external tank that are now formally classified as "probable/catastrophic" in NASA's integrated risk matrix. That means it is probable that the so-called ice-frost ramps will shed debris with catastrophic results over the life of the program.

Griffin told reporters today he did not agree with the probable/catastrophic classification and added that even in a worst-case scenario, the astronauts would not be in immediate danger. Because of new cameras and other sensors, any damage would be seen and the crew could either attempt repairs or move aboard the space station to await rescue by another shuttle crew.

If It Talks Like A Duck And Walks Like A Duck...

It was most probably a duck.

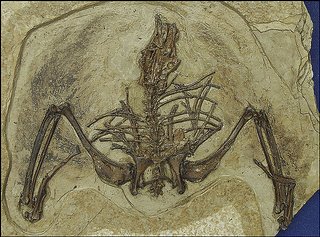

Paleontologists have unearthed the exquisitely preserved fossils of what is the oldest known ancestor of modern birds, a loonlike swimmer and flier that flourished in lake country 110 million years ago in what is today northwest China.Anybody for calling it Peking Duck?

The fossils included five headless but otherwise nearly complete skeletons that show the outlines of soft tissues, including feathers and ducklike webbing between the toes. Researchers said the find suggested modern birds may have evolved from aquatic ancestors.

An international team led by Hai-lu You, of the Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, found the fossils, known as Gansus yumenensis , in Gansu province near Changma, a mountain community about 1,200 miles west of Beijing. Results of their research are reported today in the journal Science.

"They were clearly able to fly but were also adaptable for swimming and diving," said team member Matthew C. Lamanna, of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. "We don't know what they ate because we don't have a skull, but the legs and feet are those of a diver. He had a powerful kick stroke."

No comments:

Post a Comment